2. 水产科学国家级实验教学示范中心 上海海洋大学 上海 201306;

3. 莱州市明波水产有限公司 烟台 261400

2. International Research Center for Marine Biosciences, Shanghai Ocean University, Ministry of Science and Technology, Shanghai 201306;

3. Laizhou Mingbo Aquatic Co., Ltd., Yantai 261400

斑石鲷(Oplegnathus punctatus)属于鲈形目、石鲷科、石鲷属,主要分布在太平洋东北部,朝鲜、日本、中国等地沿海地区。因其营养丰富、经济价值高,成为一种新兴的工厂化养殖鱼类。但在斑石鲷大规模养殖过程中病害频发,严重影响斑石鲷的产业发展。因此,研究病毒感染与免疫的分子机制,对于斑石鲷病害防控具有重要意义。

通过对某养殖场患病或死亡斑石鲷的PCR检测,可以扩增出明亮的虹彩病毒特有的条带。因此,认为这些斑石鲷携带虹彩病毒,并推测虹彩病毒可能与斑石鲷的死亡有关。虹彩病毒科包括5个属:细胞肿大病毒属、蛙病毒属、淋巴肿大病毒属、虹彩病毒属和绿虹彩病毒属等。其中,感染鱼类的主要是细胞肿大病毒属中的真鲷虹彩病毒(RSIV)和脾肾坏死病毒(ISKNV),它们可以感染多种海洋鱼类,感染后死亡率极高(Nakajima et al, 1998; He et al, 2001)。虹彩病毒是一种大型二十面体病毒,具有线性双链DNA基因组(Goorha et al, 1984)。在一些亚洲国家,细胞肿大病毒导致多种海洋物种在高水温下死亡(Inoue et al, 1992; Nakajima et al, 1994; Chua et al, 1994; Matsuoke et al, 1996; Miyata et al, 2010; Chou et al, 1998)。在韩国,1998年首次在南部沿海地区发现条石鲷虹彩病毒感染(Jung et al, 2000)。疾病的最初症状是进食量减少,嗜睡,身体颜色异常,鳃有淤点,以及脾脏、鳃和消化道的病变。在疾病的末期,患病鱼在笼子边缘无规律游动(Inoue et al, 1992; Jung et al, 2000; Gibson-Kueh et al, 2003; He et al, 2000; Miyata et al, 1997)。受虹彩病毒感染的鱼的特征是脾脏增大,脾脏、鳃、肾、心脏和肝脏中存在嗜碱性细胞增大的现象,并导致肾和脾造血组织坏死(Nakajima et al, 1998; Oshima et al, 1998; Qin et al, 2002; Jung et al, 2000)。虹彩病毒对斑石鲷养殖业危害巨大,因此,亟需从分子机制角度对斑石鲷虹彩病毒病进行防治。

TGF-β是调节复杂免疫反应的主要分子开关,在免疫过程中起促进和抑制的双重调节作用。转化生长因子β超家族(TGF-βS)属于多功能生长因子的超家族,主要包括5个成员(TGF-β 1~5) (Roberts et al, 1990; Kehrl et al, 1986)。体内绝大部分组织和细胞都能产生TGF-β及其受体(Le et al, 2005),在成纤维细胞、巨噬细胞和血小板中表达量较高(Takehara, 2000; Thompson et al, 1989),其广泛参与体内各种生理生化功能的调节,包括哺乳动物胚胎发育,两栖动物、昆虫的骨骼发育,伤口愈合、免疫以及成人的炎症反应,调节细胞增殖、分化和生长(Senturk et al, 2010),并能调节包括干扰素γ和肿瘤坏死因子α在内的其他生长因子的表达和激活,其中,TGF-β1含量最高且功能最为广泛。

目前,TGF-β1在鱼类中的研究主要集中在基因克隆和对免疫细胞调节方面,先后在虹鳟(Oncorhynchus mykiss) (Daniels et al, 1999)、斑马鱼(Danio rerio) (Kohli et al, 2003)、海鲷(Sparus aurata)(Tafalla et al, 2003)、草鱼(Ctenopharyngodon idella) (Yang et al, 2008)中克隆得到TGF-β1;在鱼类免疫细胞中的研究表明,通过用LPS刺激草鱼体外培养的单核巨噬细胞,发现TGF-β1抑制了炎性细胞因子如肿瘤坏死因子(tnfa)、白细胞介素(il1b)、肌苷(inos)和白细胞介素(il8) mRNA水平的表达(Wei et al, 2015)。金鱼(Carassius auratus L.) TGF-β1抑制TNF-α激活的巨噬细胞中的一氧化氮的生成(Haddad et al, 2008),从而抑制巨噬细胞的活化。草鱼TGF-β1显著降低草鱼头部肾白细胞(hkls)的活性(Yang et al, 2012)。这些研究表明,TGF-β1主要通过抑制促炎性因子的表达来发挥抗炎症作用,因为过度炎症可能导致组织损伤和广泛的慢性疾病,在哺乳动物中造成如关节炎、炎症性肠病和哮喘等(Foster et al, 2009)。TGF-β1已被证明能够抑制toll样受体下游的炎症信号,在炎症的消退中起关键作用(Han et al, 2005; Serhan et al, 2005; Yoshimura et al, 2010)。然而,TGF-β1在某些研究中呈现出截然相反的作用,如草鱼体内TGF-β1下调LPS/PHA刺激造成的外周血淋巴细胞增殖,而TGF-β1在同一细胞中的刺激作用则出现与之相反的情况(Yang et al, 2010)。TGF-β1在哺乳动物的免疫应答中同样发挥双重作用。如在癌细胞发展初期起到抑制作用,而在癌细胞的侵袭和扩散过程中起促进作用。这些研究不仅可以将TGF-β1看作是硬骨鱼类的免疫调节因子,还表明TGF-β1在脊椎动物进化过程中保持基本相近的免疫功能。然而,有关鱼类TGF-β1参与炎症调节的机制仍然缺乏研究。实际上,到底是什么机制介导其对免疫应答的抑制作用,仍然没有详细的阐释。

本文主要研究了TGF-β1基因在斑石鲷健康组织中的相对表达量以及斑石鲷感染虹彩病毒后该基因在4种不同免疫组织中相对表达量的差异,希望能为进一步深入了解TGF-β1基因在斑石鲷免疫调节中起的作用提供借鉴。

1 材料与方法 1.1 实验材料正常组织:健康、体重为(300±10) g的斑石鲷由莱州明波水产有限公司提供,实验前,在水箱中暂养3 d (24℃~26℃)。麻醉后,取3条鱼进行解剖,取肝脏、脾脏、肾脏、头肾、心脏、鳃、胃、肠和皮肤组织,立即放入液氮保存,随后将样品转移到-80℃保存,用于后续的RNA提取。

斑石鲷虹彩病毒感染及样品采集:健康、体重为(150±10) g的斑石鲷,由莱州明波水产有限公司提供,实验前暂养3 d (24℃~26℃)。麻醉后,腹腔注射斑石鲷虹彩病毒液(由华南农业大学秦启伟教授提供),每尾100 μl (109拷贝数)。虹彩病毒感染后,在0、4、7、10 d时间点取样,每个时间点取3条鱼,每条鱼取肝脏、脾脏、肾脏和头肾4个组织。取完的组织立即放入液氮中,随后放入-80℃冰箱中冷冻保存,以待后续的DNA和RNA提取。

1.2 RNA提取和cDNA的合成本实验使用Trizol法对样品的RNA进行提取,包括所有健康组织和所有感染后的样品。用琼脂糖凝胶电泳对提取的RNA进行检测,使用Gene Quant Pro RNA/DNA分光光度计测定提取的RNA的浓度。将鉴定合格的RNA,使用cDNA反转录试剂盒(TaKaRa)反转录合成cDNA,再用琼脂糖凝胶电泳检测cDNA的质量。使用RACE试剂盒(TaKaRa),按照说明合成RACE-Ready-cDNA,作为扩增5'和3'非翻译区(Untranslated Region, UTR)的模板。

1.3 TGF-β1基因全长cDNA与基因组序列的克隆 1.3.1 中间片段的验证根据斑石鲷转录组测序结果,获得TGF-β1基因的部分cDNA序列,使用Primer 5.0软件设计引物(TGF-β1-F/TGF-β1-R) (表 1),分别将9个不同组织(肝脏、脾脏、肾脏、头肾、心脏、鳃、胃、肠和皮肤)的cDNA模板进行混合,使用混合模板进行PCR扩增。总体系为15 μl: Mix (TaKaRa) 7.5 μl,TGF-β1-F 1 μl,TGF-β1-R 1 μl,ddH2O 4.5 μl,模板cDNA 1 μl。反应程序:95℃预变性5 min;95℃ 30 s,58℃ 30 s,72℃ 60 s,共40个循环;72℃ 7 min;4℃保存。

将得到的PCR产物进行琼脂糖凝胶电泳检测,PCR产物与目的片段大小一致,将目的片段切下,使用胶回收试剂盒(诺唯赞, 南京)对目的片段进行回收纯化,将回收产物连接到pEASY-T1载体(全式金, 北京),转化到Trans-T1感受态细胞(全式金, 北京)中,加入无抗LB液体培养基,振荡培养1 h,涂板,37℃过夜培养(12~16 h),挑取6个克隆送到北京睿博兴科生物技术有限公司(青岛区)测序。

1.3.2 5'和3'RACE克隆根据已经验证正确的部分cDNA序列,分别在序列两端设计5' (TGF-β1-5'- GSP/TGF-β1-5'-NGSP)和3' (TGF-β1-3'-GSP/ TGF-β1-3'-NGSP) RACE引物(表 1)。使用巢氏PCR扩增5'/3'UTR。第一轮反应体系为10 μl,使用TaKaRa LA TaqTM Hot Start Version试剂盒,按照使用说明的比例加样混合,进行Touchdown PCR程序反应。将第一轮PCR反应的产物稀释20倍作为模板,随后进行第二轮普通PCR扩增反应。反应体系为50 μl,同上按照比例加样混合后进行第二轮普通PCR反应。将得到的PCR产物根据1.3.1中间片段验证的方法进行测序(Wang et al, 2019)。

|

|

表 1 本实验所用到的引物 Tab.1 Primers used in this study |

提取3条斑石鲷的脾脏组织的DNA,以此为模板,验证TGF-β1的基因组。方法与1.3.1中间片段的验证类似,引物(TGF-β1-GM- F1/TGF-β1-GM-R1, TGF-β1-GM-F2/TGF-β1-GM-R2, TGF-β1-GM-F3/TGF-β1-GM-R3, TGF-β1-GM-F4/TGF- β1-GM-R4和TGF-β1-GM-F5/TGF-β1-GM-R5)退火温度改设为55℃,延伸时间设为5 min。

1.4 生物学分析及系统发育树的构建使用NCBI对克隆得到的TGF-β1基因的全长cDNA序列进行分析,预测其开放阅读框(ORF)和氨基酸序列,并推导出其蛋白的分子量和等电点(图 1)。使用网站(http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/)对翻译的氨基酸序列进行分析,包括信号肽,氨基酸序列跨膜结构域。

|

图 1 斑石鲷TGF-β1 cDNA序列和推测的氨基酸序列 Fig.1 Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of O. punctatus TGF-β1 推导的氨基酸序列显示在核苷酸序列下方,用大写字母表示。方框所示为起始密码子(ATG)、星号(*)所示为终止密码子(TGA);下划线(—)所示为TGF-β家族结构域;蓝色下划线(—)所示为终止信号;黄色下划线(—)所示为polyA结构 The deduced amino acid sequence is shown below the nucleotide sequence and expressed in capital letters. The starting codon (ATG), asterisk (*) and termination codon (TGA) are shown in the box, the underline (—) is shown in the TGF-beta family domain, the blue underline (—) is shown in the termination signal, and the Yellow underline (—) is shown in the polyA structure |

在NCBI中搜索TGF-β1基因放入同源氨基酸序列并预测其功能结构域。使用DNAMAN软件对TGF-β1进行氨基酸多重比对,通过MEGA 7.0软件完成其生物系统进化树构建。

1.5 TGF-β1基因的相对表达量检测通过使用实时荧光定量PCR(qRT-PCR)检测健康的斑石鲷不同组织中TGF-β1基因的相对表达量;经虹彩病毒感染刺激后4个不同时间点、4个不同组织(肝、肾、脾和头肾)的相对表达量的变化。根据得到的ORF序列设计实时荧光定量PCR引物(TGF-β1- qRT-F/TGF-β1-qRT-R, 表 1),再以β-actin基因(β- actin-F/β-actin-R, 表 1)作为内参基因,每个样品设置3个生物学重复,按照TaKaRa SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM说明书介绍的方法进行TGF-β1基因的定量分析。根据测得的Ct值(Ct取3个平行样品的平均值),利用2-ΔΔCt法计算TGF-β1基因相对表达量,实验得到的数据均采用SPSS软件进行方差分析,设定P < 0.05为差异显著。使用Origin Pro 8软件将定量结果作图(Wang et al, 2018)。

2 结果与分析 2.1 斑石鲷TGF-β1基因序列特征斑石鲷TGF-β1基因的cDNA全长为3157 bp,开放阅读框长1167 bp,编码388个氨基酸,5'非编码区长712 bp,3'非编码区长1278 bp,相对分子质量为44.32 kDa,预测等电点为8.178。对TGF-β1基因的氨基酸序列进行分析,发现该基因没有信号肽,也没有跨膜区,含有1个TGF-β前导肽,为第19~260个氨基酸;含有1个TGF-β结构域,为第291~388个氨基酸,长98个氨基酸。

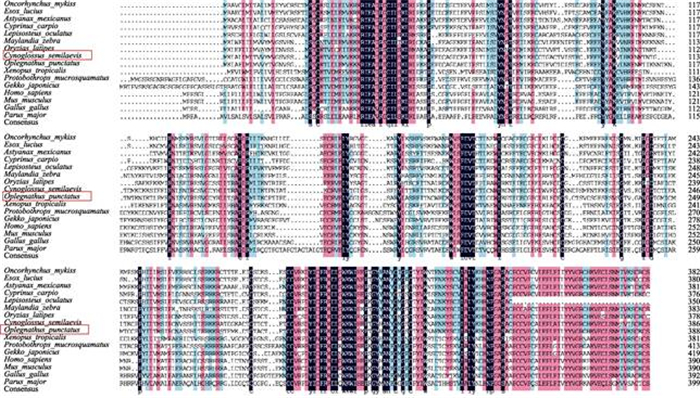

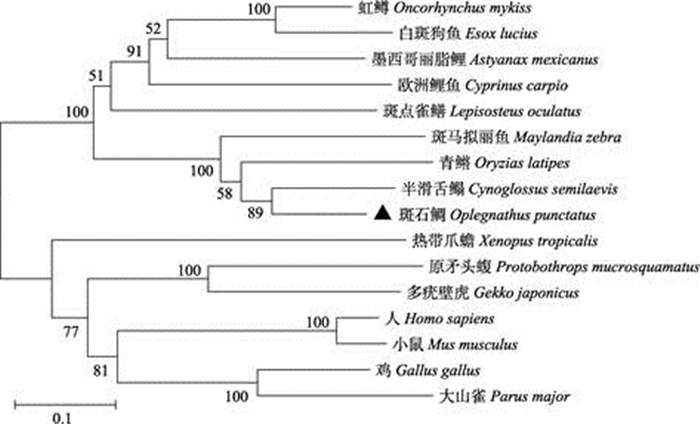

2.2 系统进化树分析和氨基酸多序列比对将斑石鲷的TGF-β1基因对应的氨基酸序列通过NCBI的Protein Blast比对,从NCBI上下载其他物种TGF-β1基因的氨基酸序列,鸟纲2种:鸡(Gallus gallus) (XP_025000221.1)、大山雀(Parus major) (XP_015471764.1);哺乳纲2种:人(Homo sapiens) (NP_000651.3)、小鼠(Mus musculus) (NP_035707.1);爬行纲2种:多疣壁虎(Gekko japonicus) (XP_ 015282748.1)、原矛头蝮(Protobothrops mucrosquamatus) (XP_015680068.1);两栖纲1种:热带爪蟾(Xenopus tropicalis) (XP_002939433.1);鱼纲9种:青鳉(Oryzias latipes) (XP_004075270.1)、墨西哥丽脂鲤(Astyanax mexicanus) (XP_022531678.1)、斑点雀鳝(Lepisosteus oculatus) (XP_015196176.1)、虹鳟(O. mykiss) (XP_021447007.1)、白斑狗鱼(Esox lucius) (XP_010868815.1)、半滑舌鳎(Cynoglossus semilaevis) (XP_008307032.1)、欧洲鲤鱼(Cyprinus carpio) (XP_018927916.1)、斑马拟丽鱼(Maylandia zebra) (XP_004569626.1),共计16种。多重氨基酸序列比对结果显示,斑石鲷和其他鱼类物种TGF-β1氨基酸序列相对保守,其中,特有的TGF-β结构域更为保守(图 2)。系统进化树显示,鱼纲聚为一大支,青鳉(鳉形目青鳉科)、斑石鲷(鲈形目石鲷科)、半滑舌鳎(鲽形目舌鳎科)、斑马拟丽鱼(鲈形目慈鲷科)聚为一支;欧洲鲤(鲤形目鲤科)、虹鳟(鲑形目鲑科)、白斑狗鱼(狗鱼目狗鱼科)、墨西哥丽脂鲤(脂鲤目脂鲤科)聚为一支。鸟纲的鸡(鸡形目雉科)和大山雀(雀形目山雀科)聚为一支;哺乳纲的小鼠(鼠目啮齿科)和人(灵长目人科)聚为一支;爬行纲的多疣壁虎(有鳞目壁虎科)、原矛头蝮(有鳞目蝰科)聚为一支;两栖纲的热带爪蟾(无尾目负子蟾科)单独聚为一支(图 3)。经基因组分析发现,斑石鲷与半滑舌鳎的基因组都包含6个外显子和5个内含子,白斑狗鱼和人则含有7个外显子和6个内含子(图 4)。

|

图 2 斑石鲷与其他物种TGF-β1氨基酸序列多重比对 Fig.2 Multiple alignment of the deduced amino acids of TGF-β1 among O. punctatus and other different species |

|

图 3 斑石鲷TGF-β1与其他物种TGF-β1系统进化分析 Fig.3 Phylogenetic analysis of TGF-β1 among O. punctatus and other different species |

|

图 4 斑石鲷、白斑狗鱼、半滑舌鳎和人的TGF-β1基因结构

Fig.4 Structure of TGF-β1 gene in O. punctatus, E.Lucius, C. semilaevis and H. sapiens

黄色方框代表外显子,直线代表内含子。 exon

exon  intron

The yellow box represents the exon and the straight line represents the intron

斑石鲷(O. punctatus): 1: 332 bp; 2: 291 bp; 3: 239 bp; 4: 155 bp; 5: 116 bp; 6: 50 bp; intron

The yellow box represents the exon and the straight line represents the intron

斑石鲷(O. punctatus): 1: 332 bp; 2: 291 bp; 3: 239 bp; 4: 155 bp; 5: 116 bp; 6: 50 bp; a: 4411 bp; b: 164 bp; c: 541 bp; d: 1332 bp; e: 113 bp. 白斑狗鱼(E. lucius): 1: 1295 bp; 2: 270 bp; 3: 80 bp; 4: 147 bp; 5: 154 bp; 6: 115 bp; 7: 532 bp; a: 4295 bp; b: 198 bp; c: 107 bp; d: 159 bp; e: 153 bp; f: 131 bp. 半滑舌鳎(C. semilaevis): 1: 2492 bp; 2: 279 bp; 3: 242 bp; 4: 150 bp; 5: 115 bp; 6: 60bp; a: 5351 bp; b: 79 bp; c: 154 bp; d: 1326 bp; e: 102 bp. 人(H. sapiens): 1: 553 bp; 2: 162 bp; 3: 121 bp; 4: 80 bp; 5: 160 bp; 6: 173 bp; 7: 304 bp; a: 4234 bp; b: 3429 bp; c: 2497 bp; d: 128 bp; e: 9590 bp; f: 903 bp. |

qRT-PCR健康组织的表达结果显示,TGF-β1基因在斑石鲷各个组织中均有表达,其中,在肝脏、头肾、肠、皮肤、鳃中表达量较高,头肾最高;在脾脏、肾脏、胃、脑中表达量较低,脾脏最低(图 5)。

|

图 5 TGF-β1基因在健康斑石鲷组织中的相对表达量

Fig.5 The relative expression of TGF-β1 gene in normal tissues of O.punctatus

a、b和c表示在SPSS 19.0软件中的Duncan分组。 同一字母表示无显著差异(P > 0.05),不同字母表示 显著差异(P < 0.05)。下同 The letters of 'a, b and c' indicated the Duncan grouping in SPSS 19.0 software. The same letters indicate no significant difference (P > 0.05), the different letters indicate significant difference (P < 0.05). The same applies below |

在肝脏中呈现出先升高后降低的趋势,在4 d时表达量最高,约是0 d的2.7倍;在头肾中呈现波动的趋势,0~4 d升高,第4天是0 d的1.94倍,4~7 d降低,7~10 d再度升高,10 d时表达量最高,是0 d的2.5倍;脾脏与头肾的趋势类似,不过在4 d时表达量最高,是0 d的3.1倍;在肾脏中呈现先下降后升高的趋势,0~7 d下降,7~10 d升高,其中,7 d时表达量最低,是0 d的0.38倍(图 6)。

|

图 6 斑石鲷感染斑石鲷虹彩病毒4种组织(肝脏、肾脏、头肾和脾脏)中TGF-β1基因的相对表达量 Fig.6 Relative expression of TGF-β1 gene in four tissues (liver, spleen, kidney, and head kidney) of O. punctatus at different time points after SKIV infection |

本研究通过PCR和RACE技术克隆得到了斑石鲷TGF-β1基因的cDNA全长序列,研究了斑石鲷在健康组织和响应虹彩病毒刺激后TGF-β1相对表达量的变化。对TGF-β1基因的多重氨基酸序列比对结果分析,发现参与比对的不同物种TGF-β1蛋白结构比较相似,都包含1个前导肽(第19~260氨基酸)和1个TGF-β结构域(第291~388氨基酸)。但相对而言,不同鱼类之间TGF-β序列更为相似,而在不同纲之间差异较大,例如,斑石鲷与人类TGF-β1氨基酸序列相似度为47.34%,与半滑舌鳎相似度为76.67%。TGF-β蛋白起初是以未激活的形式从细胞中分泌出来的,称为休眠TGF-β或小休眠复合体。对克隆得到的TGF-β1基因的氨基酸序列分析证明其包含1个前导肽。TGF-β家族有9个半胱氨酸,这9个半胱胺酸中的8个会每2个为1组形成半胱氨酸结(Cysteine knot),这个结构是整个TGF-β超家族所共有的特征,第9个半胱氨酸会通过共价的二硫键与另外一个次单元的半胱氨酸形成二聚体。其他的TGF-β结构主要以非共价的疏水性相互作用力(Hydrophobic interactions)形成其二级结构。第5个与第6个半胱氨酸之间含有最多的氨基酸变异区域,而这段区域是使TGF-β分子暴露在外,使不同的TGF-β与不同受体分子相互识别并相互结合的区域(Daopin et al, 1992)。

鱼类免疫主要以先天性免疫为主。大马哈鱼(Oncorhynchus keta)抗体的产生需要4~6周时间,并且依赖温度,然而病原体的侵袭在短短几天内就可以造成鱼体死亡,因此,鱼类抗病原体的免疫应答中,先天性免疫在感染初期发挥主要作用,由肾脏、脾脏及粘膜相关淋巴组织(存在于鳃、消化道等富含粘膜层的组织中)执行(Ellis, 2001);另外,在许多物种的肝脏移植研究中发现,肝脏也具有免疫调节功能(Qian et al, 1997)。对斑石鲷健康组织相对表达量分析发现,TGF-β1基因在斑石鲷各个组织中均有表达,并且具有组织特异性,其中,头肾表达量最高,这与罗非鱼(Oreochromis niloticus)健康组织中的情况一致(Zhan et al, 2015),在肝脏、肠、皮肤和鳃中表达量较高,可能是由于TGF-β1主要分布在细胞分化旺盛或与外界有直接接触并且含有大量淋巴组织的外周免疫器官之中,这些组织含有大量的未被激活的TGF-β1,作为免疫应答的启动因子储存。TGF-β1在斑石鲷头肾、脾脏和肝脏中相对表达量的变化则有可能与TGF-β1在免疫过程中发挥的双重调节作用有关。其中,病毒感染后的第4天斑石鲷开始发病,头肾、脾脏、肝脏中的上调可能代表TGF-β1是促进免疫应答的,一些研究表明,TGF-β可以在感染部位招募单核细胞和中性粒细胞,触发促炎性细胞因子表达(如TNF-α、IL-γ等),激活白细胞促进其对感染细胞的吞噬和抗原的呈递,放大炎症反应(Li et al, 2006; McGeachy et al, 2007; Wan et al, 2007),这可以帮助机体对抗病毒的侵袭;随后表达下降(第7天),但在第10天,脾脏和头肾再度上调可能是与其抑制或终止免疫应答有关,有研究证明,TGF-β可以直接下调其他促炎性细胞因子的表达,参与炎症的消退(Roberts et al, 1993),可以避免机体过度炎症反应引起的损伤,TGF-β的双重调节机制可能依赖于作用部位的体液环境,受调控细胞类型和自身浓度梯度影响。无乳链球菌(Streptococcus agalactiae)感染罗非鱼的实验中,头肾TGF-β1也表现出在0~4 d升高,随后下降的趋势,但其在10 d时并未再度升高,与本研究肝脏情况一致,VHSV (Viral haemorrhagic septicemia virus)感染虹鳟的实验中,TGF-β1在头肾组织中也呈现先升高后下降的趋势,非致病性病毒株感染组在第3天达到峰值,致病性病毒株感染组在第5天达到峰值(Maehr et al, 2013)。至于病毒感染后肾脏中TGF-β1表达一直呈下调趋势,这种变化则十分有趣。由于虹彩病毒主要感染部位是脾脏和肾脏,这可能是由于在感染后主要是头肾而非整个肾脏发挥主要免疫作用而造成的。哈维氏弧菌(Vibrio harveyi)感染半滑舌鳎的实验中发现,感染后的72 h内,半滑舌鳎肝脏、脾脏和肾脏中TGF-β1呈现先上升后下降的表达趋势,不同组织达到峰值的时间并不相同,肝脏48 h、脾脏24 h、肾脏12 h (李雪等, 2016),而本研究中TGF-β1表达量在第4天时出现显著升高(肝脏、脾脏和肾脏),随后回落,这可能是由于感染初期病毒处于潜伏期,机体免疫应答处于持续增强阶段,到第4天时达到较高水平,随后,随着机体免疫功能的自我调节,TGF-β1的表达水平逐渐回落。本研究发现,TGF-β1可能参与了斑石鲷对虹彩病毒的免疫应答,并在其中发挥一定作用,希望能为深入研究TGF-β1基因在斑石鲷免疫应答过程中发挥的作用提供借鉴。

4 结论斑石鲷TGF-β1基因cDNA序列与半滑舌鳎TGF-β1基因序列最相似。健康斑石鲷中,TGF-β1基因主要在头肾、肝和肠中表达;虹彩病毒感染后,TGF-β1基因表达量显著上调,揭示了TGF-β1可能与斑石鲷抗虹彩病毒免疫应答有关。

Chou HY, Hsu CC, Peng TY. Isolation and characterization of a pathogenic iridovirus from cultured grouper (Epinephelus sp. ) in Taiwan. Fish Pathology, 1998, 33: 201-206 DOI:10.3147/jsfp.33.201 |

Chua FHC, Ng ML, Ng KL, et al. Investigation of outbreaks of a novel disease, 'Sleepy Grouper Disease' affecting the brown-spotted grouper, Epinephelus tauvina Forskal. Journal of Fish Diseases, 1994, 17: 417-427 DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2761.1994.tb00237.x |

Daniels GD, Secombes CJ. Genomic organization of rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss TGF-beta. Developmental and Comparative Immunology, 1999, 23(2): 139-147 DOI:10.1016/S0145-305X(98)00051-2 |

Daopin S, Piez K, Ogawa Y, et al. Crystal structure of transforming growth factor-beta 2: An unusual fold for the superfamily. Science, 1992, 257(5068): 369-373 DOI:10.1126/science.1631557 |

Ellis AE. Innate host defense mechanisms of fish against viruses and bacteria. Developmental and Comparative Immunology, 2001, 25(8–9): 827-839 |

Foster SL, Medzhitov R. Gene-specific control of the TLR-induced inflammatory response. Clinical Immunology, 2009, 130(1): 7-15 |

Gibson-Kueh S, Netto P, Ngoh-Lim GH, et al. The pathology of systemic iridoviral disease in fish. Journal of Comparative Pathology, 2003, 129(2–3): 111-119 |

Goorhai R, Dixit P. A temperature-sensitive (TS) mutant of frog virus 3 (FV3) is defective in second-stage DNA replication. Virology, 1984, 136(1): 186-195 DOI:10.1016/0042-6822(84)90258-7 |

Haddad G, Hanington PC, Wilson EC, et al. Molecular and functional characterization of goldfish (Carassius auratus L. ) transforming growth factor beta. Developmental and Comparative Immunology, 2008, 32(6): 654-663 |

Han J, Ulevitch RJ. Limiting inflammatory responses during activation of innate immunity. Nature Immunology, 2005, 6(12): 1198-1205 DOI:10.1038/ni1274 |

He JG, Wang SP, Zeng K, et al. Systemic disease caused by an iridovirus like agent in cultured mandarin fish, Siniperca chuatsi (Basilewsky), in China. Journal of Fish Diseases, 2001, 23(3): 219-222 |

Inoue K, Yamano K, Maeno Y, et al. Iridovirus infection of cultured red sea bream, Pagrus major. Fish Pathology, 1992, 27: 19-27 DOI:10.3147/jsfp.27.19 |

Jung SJ, Oh MJ. Iridovirus-like infection associated with high mortalities of striped beakperch, Oplegnathus fasciatus (Temminck et Schlegel), in southern coastal areas of the Korean peninsula. Journal of Fish Diseases, 2000, 23(3): 223-226 DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2761.2000.00212.x |

Kehrl JH. Production of transforming growth factor beta by human T lymphocytes and its potential role in the regulation of T cell growth. Journal of Experimental Medicine, 1986, 163(5): 1037-1050 DOI:10.1084/jem.163.5.1037 |

Kohli G, Hu S, Clelland E, et al. Cloning of transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-beta 1) and its type Ⅱ receptor from zebrafish ovary and role of TGF-beta 1 in oocyte maturation. Endocrinology, 2003, 144(5): 1931-1941 DOI:10.1210/en.2002-0126 |

Le Y, Yu X, Ruan L, et al. The immunopharmacological properties of transforming growth factor beta. International Immunopharmacology, 2005, 5(13–14): 1771-1782 |

Li MO, Wan YY, Shomyseh S, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta regulation of immune responses. Annual Review of Immunology, 2006(24): 99-146 |

Li X, Chen SL, Yang CG, et al. Molecular cloning and expression analysis of transforming growth factor TGF-β1 and TGF-β3 in half-smooth tongue sole (Cynoglossus semilaevis) following stimulation with Vibrio harveyi. Journal of Agricultural Biotechnology, 2016, 24(6): 889-898 |

李 雪, 陈 松林, 杨 长庚, et al. 半滑舌鳎转化生长因子TGF-β1和TGF-β3基因的克隆及受哈维氏弧菌感染后表达分析. 农业生物技术学报, 2016, 24(6): 889-898 |

Maehr T, Costa MM, Vecino JL, et al. Transforming growth factor-β1b: A second TGF-β1 paralogue in the rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) that has a lower constitutive expression but is more responsive to immune stimulation. Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 2013, 34(2): 420-432 DOI:10.1016/j.fsi.2012.11.011 |

Matsuoke S, Inouye K, Nakajima K. Cultured fish species affected by red sea bream iridoviral disease from 1991 to 1995. Fish Pathology, 1996, 31(4): 233-234 DOI:10.3147/jsfp.31.233 |

McCartney-Francis NL, Frazier-Jessen M, Wahl SM. TGF-beta: A balancing act. International Reviews of Immunology, 1998, 16(5–6): 553-580 |

McGeachy MJ, Cua DJ. T cells doing it for themselves: TGF-beta regulation of Th1 and Th17 cells. Immunity, 2007, 26(5): 547-549 DOI:10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.003 |

Miyata M, Matsuno K, Jung SJ, et al. Genetic similarity of iridoviruses from Japan and Thailand. Journal of Fish Diseases, 1997, 20(2): 127-134 DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2761.1997.d01-115.x |

Nakajima K, Sorimachi M. Biological and physico-chemical properties of the iridovirus isolated from cultured red sea bream, Pagrus major. Fish Pathology, 1994, 29(1): 29-33 |

Nakajima K, Inouye K, Sorimachi M. Viral diseases in cultured marine fish in Japan. Fish Pathology, 1998, 33(4): 181-188 DOI:10.3147/jsfp.33.181 |

Oshima S, Hata JI, Hirasawa N, et al. Rapid diagnosis of red sea bream iridovirus infection using the polymerase chain reaction. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 1998, 32(2): 87-90 |

Qian S, Thai NL, Lu L, et al. Liver transplant tolerance: mechanistic insights from animal models, with particular reference to the mouse. Transplant Reviews, 1997, 11(3): 151-164 DOI:10.1016/S0955-470X(97)80015-8 |

Qin QW, Shi C, Gin KY, et al. Antigenic characterization of a marine fish iridovirus from grouper, Epinephelus spp. Journal of Virological Methods, 2002, 106(1): 89-96 DOI:10.1016/S0166-0934(02)00139-8 |

Roberts AB, Rosa F, Roche NS, et al. Isolation and characterization of TGF-beta 2 and TGF-beta 5 from medium conditioned by Xenopus XTC cells. Growth Factors, 1990, 2(2–3): 135-147 |

Roberts AB, Sporn MB. Physiological actions and clinical applications of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). Growth Factors, 1993, 8(1): 1-9 DOI:10.3109/08977199309029129 |

Senturk S, Mumcuoglu M, Gursoy-Yuzugullu O, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta induces senescence in hepatocellular carcinoma cells and inhibits tumor growth. Hepatology, 2010, 52(3): 966-974 DOI:10.1002/hep.23769 |

Serhan CN, Savill J. Resolution of inflammation: The beginning programs the end. Nature Immunology, 2005, 6(12): 1191-1197 DOI:10.1038/ni1276 |

Tafalla C, Aranguren R, Secombes CJ, et al. Molecular characterisation of sea bream (Sparus aurata) transforming growth factor β1. Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 2003, 14(5): 405-421 DOI:10.1006/fsim.2002.0444 |

Takehara K. Growth regulation of skin fibroblasts. Journal of Dermatological Science, 2000, 24(Supplement 1): S70-S77 |

Thompson NL, Flanders KC, Smith JM, et al. Expression of transforming growth factor-β1 in specific cells and tissues of adult and neonatal mice. Journal of Cell Biology, 1989, 108(2): 661-669 DOI:10.1083/jcb.108.2.661 |

Wan YY, Flavell RA. 'Yin-Yang' functions of transforming growth factor-β and T regulatory cells in immune regulation. Immunological Reviews, 2007, 220(1): 199-213 DOI:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00565.x |

Wang RQ, Wang N, Wang RK, et al. The identification of tyrp1a and tyrp1b in Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) and the regulation study of tyrp1a and mmu-miR-143- 5p_R+2. Progress in Fishery Sciences, 2018, 39(2): 49-58 |

王 若青, 王 娜, 王 仁凯, et al. 牙鲆tyrp1a和tyrp1b的鉴定及tyrp1a与mmu-miR-143-5p_R+2的调控关系. 渔业科学进展, 2018, 39(2): 49-58 |

Wang SY, Wang L, Chen ZF, et al. Cloning and expression analysis of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR) gene in the half smooth tongue sole (Cynoglossus semilaevis). Progress in Fishery Sciences, 2019, 40(2): 51-57 |

王 双艳, 王 磊, 陈 张帆, et al. 半滑舌鳎多聚免疫球蛋白受体(pIgR)基因的克隆和表达分析. 渔业科学进展, 2019, 40(2): 51-57 |

Wei H, Yin LC, Feng SY, et al. Dual-parallel inhibition of IL-10 and TGF-β1 controls LPS-induced inflammatory response via NF-κB signaling in grass carp monocytes/macrophages. Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 2015, 44(2): 445-452 DOI:10.1016/j.fsi.2015.03.023 |

Yang M, Wang Y, Wang X, et al. Characterization of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) Foxp1a/1b/2: Evidence for their involvement in the activation of peripheral blood lymphocyte subpopulations. Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 2010, 28(2): 289-295 DOI:10.1016/j.fsi.2009.11.007 |

Yang M, Wang X, Chen D, et al. TGF-β1 exerts opposing effects on grass carp leukocytes: Implication in teleost immunity, receptor signaling and potential self-regulatory mechanisms. PLoS One, 2012, 7(4): e35011 DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0035011 |

Yang M, Zhou H. Grass carp transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-beta1): Molecular cloning, tissue distribution and immunobiological activity in teleost peripheral blood lymphocytes. Molecular Immunology, 2008, 45(6): 1792-1798 DOI:10.1016/j.molimm.2007.09.027 |

Yoshimura A, Wakabayashi Y, Mori T. Cellular and molecular basis for the regulation of inflammation by TGF-beta. Journal of Biochemistry, 2010, 147(6): 781-792 DOI:10.1093/jb/mvq043 |

Zhan XL, Ma TY, Wu JY, et al. Cloning and primary immunological study of TGF-β1 and its receptors TβR Ⅰ/TβR Ⅱ in tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Developmental and Comparative Immunology, 2015, 51(1): 134-140 DOI:10.1016/j.dci.2015.03.008 |