贝类增养殖是海水养殖业的重要支柱之一,具有重要的社会、经济和生态价值。近年来,中国海水贝类养殖的年产量呈稳步上升趋势; 2018年,中国海水贝类养殖产量达1444万t,占海水养殖总产量的71.1%(中国渔业统计年鉴)。随着贝类养殖产业总体规模的不断扩大,养殖病害问题日益严重。据统计,2019年中国贝类养殖产业因疫病造成的经济损失高达88.7亿元(中国水生动物卫生状况报告)。受流行性疫病的影响,中国部分地区、部分种类的贝类养殖规模大幅萎缩,甚至濒临崩溃。如20世纪90年代末,中国北方养殖栉孔扇贝(Chlamys farreri)和南方养殖杂色鲍(Haliotis diversicolor supertexta),分别因感染牡蛎疱疹病毒(Ostreid herpesvirus 1, OsHV-1)和鲍疱疹病毒(Haliotid herpesvirus 1, HaHV-1)暴发大规模死亡。受此疫情影响,中国养殖栉孔扇贝年产量从发病前(1996年)的60多万t骤减到1998年不足20万t (Guo et al, 2016); 杂色鲍在全国鲍产量中的占比由发病前的65%骤降至不足5%(Wu et al, 2016)。与此同时,OsHV-1和HaHV-1病害也在其他国家频繁发生,分别引起双壳贝类和腹足贝类的大规模死亡,成为近年来威胁全球贝类养殖产业健康发展的主要疫病。本文对OsHV-1和HaHV-1 2种疱疹病毒的出现与传播、病毒特征与变异演化、致病特征与诊断技术,以及此类病毒病的防控等方面取得的重要研究进展进行总结和回顾,并展望未来软体动物疱疹病毒研究和病害防控工作的重点。

1 软体动物疱疹病毒的发现与传播 1.1 牡蛎疱疹病毒的发现及对中国贝类养殖业的危害首例贝类感染疱疹病毒的案例发现于1972年,宿主是来自美国马里兰州的一批实验用养殖美洲牡蛎(Crassostrea virginica),这也是疱疹病毒感染无脊椎动物的首例报道(Farley et al, 1972)。此次感染案例仅限于实验用贝,未对养殖和野生贝类种群造成影响。Farley等对引起感染的疱疹样病毒病原仅进行了电镜观察,未开展进一步研究。疱疹病毒对贝类养殖产业的危害真正引起人们广泛关注是1991年以来,相关流行病相继在欧洲、澳洲和南、北美洲多国发生,引起以长牡蛎(Crassostrea gigas)为代表的多种养殖双壳贝类大规模死亡(Hine et al, 1992; Renault et al, 2001b; Barbosa-Solomieu et al, 2015)。Davison等(2005)对感染法国长牡蛎幼虫的病毒粒子进行纯化、电镜观察、全基因组测序和比对分析,发现感染长牡蛎等贝类的疱疹病毒为一种新疱疹病毒。2008年,国际病毒分类委员会(ICTV)将感染双壳贝类的疱疹病毒正式命名为牡蛎疱疹病毒1 (Ostreid herpesvirus 1, OsHV-1)。我国首例因疱疹病毒感染引起的贝类致死案例发生于1997年,引起我国北方养殖栉孔扇贝在高温季节持续发生大规模死亡。根据此次疫病流行和致病特点,中国科研人员将其命名为扇贝急性病毒性坏死病(AVND)(宋微波等, 2001),对应的病原称为扇贝急性病毒性坏死病毒(AVNV) (王崇明等, 2002)。对AVNV基因组序列测定和分析结果显示,AVNV与OsHV-1基因组相似度达97%,为同一种病毒的不同变异株(Ren et al, 2013)。

与欧美等国频繁发生OsHV-1感染引起的长牡蛎死亡不同,中国受OsHV-1感染影响的贝类种类更加多元化(Bai et al, 2015),其中,受影响较大的贝类及其首次发现年份分别为:栉孔扇贝(1997年)、长牡蛎(2009年)、魁蚶(Scapharca broughtonii) (2012年)和毛蚶(Scapharca subcrenata) (2019年)。据统计,1997年暴发的AVND导致山东省2万hm2养殖栉孔扇贝60%绝产,直接经济损失约15亿元,1998年的疫情更加严重(张福绥等, 1999)。中国长牡蛎感染OsHV-1的案例最早报道于2009年,仅造成人工繁育幼虫的死亡(未发表数据)。韩国(2009年)、日本(2010年)也相继报道了长牡蛎感染OsHV-1的案例,尚未出现对其国内长牡蛎养殖产业构成严重威胁的大规模疫情(Hwang et al, 2013; Nagai et al, 2018)。近年来,中国牡蛎人工育苗比例越来越大,2019~2020年对辽宁和福建等地育苗场开展的流行病学调查结果显示,OsHV-1感染引起的牡蛎幼虫死亡事件频繁发生,发病幼虫样本病毒载量达106~107病毒拷贝/ng总DNA (未发表数据)。

2012~2018年,中国北方育苗场及出口加工企业室内暂养的魁蚶成贝频繁发生大规模死亡,经流行病学调查和病原鉴定,确定一种OsHV-1新变异株是引发魁蚶大规模死亡的病原(Bai et al, 2016; Xia et al, 2015)。魁蚶种贝死亡主要发生在升温(每天1℃)促熟过程中,当水温升高至18℃左右时出现死亡; 出口加工企业魁蚶成贝死亡发生在夏初暂养池水温达到13℃左右时。病死魁蚶普遍出现双壳闭合不全、烂鳃、出血和内脏团苍白等非典型临床症状,死亡率往往达到100%(Bai et al, 2016)。2017年,从广东省深圳市东山码头获取的毛蚶样本中检测到高载量的OsHV-1 DNA,但对产地毛蚶种群是否有影响尚不清楚(Gao et al, 2018b)。2019年,山东莱州育苗企业从山东、浙江等地引进的毛蚶种贝,在产卵前或产卵期间发生OsHV-1感染导致的大规模死亡,发病时育苗池水温约21℃(未发表数据)。以上结果提示,我国养殖的牡蛎等贝类中存在多种对OsHV-1易感的种类,贝类育苗和养殖企业应该注重防范生产过程中的贝类疱疹病毒病害。

1.2 牡蛎疱疹病毒的全球传播和分布范围与脊椎动物疱疹病毒较强的宿主专一性不同,OsHV-1的宿主范围较广,目前已知能感染13种双壳贝类(图 1),其中包括牡蛎6种:长牡蛎、欧洲牡蛎(Ostrea edulis)(Comps et al, 1993)、新西兰牡蛎(Ostrea angasi)(Hine et al, 1997)、智利牡蛎(Ostrea chilensis) (Hine et al, 1998)、福建牡蛎(Crassostrea angulata)和矮牡蛎(Ostrea stentina)(López-Sanmartín et al, 2016a); 扇贝3种:栉孔扇贝(宋微波等, 2001; 王崇明等, 2002)、欧洲大扇贝(Pecten maximus)(Arzul et al, 2001a)和海湾扇贝(Argopecten irradians)(Kim et al, 2019); 蛤仔2种:菲律宾蛤仔(Ruditapes philippinarum) (Renault et al, 2001c)和欧洲蛤仔(Ruditapes decussatus) (Arzul et al, 2001b); 蚶类2种:魁蚶(Bai et al, 2016)和毛蚶(Gao et al, 2018b)。

|

图 1 OsHV-1在全球主要国家和地区首次发现的时间及感染物种 Fig.1 The first occurence of OsHV-1 in major countries and associated mollusks 红色字体表示主要以成贝发病和死亡为主 Mollusks colored in red indicated mortalities usually occurred in adults |

截止目前,已在全球17个国家检测到OsHV-1感染病例,遍布于非洲和南极洲之外的各大洲。长牡蛎作为养殖范围最广、产量最大的贝类,也是受OsHV-1危害最严重的种类,其感染案例在17个国家均有分布,而其他贝类品种的感染案例通常只局限于一个国家。

1.3 鲍疱疹病毒发现、传播及对中国鲍养殖业的危害疱疹样病毒粒子感染腹足贝类的案例首次发现于1999年,引起中国福建东山地区杂色鲍大规模死亡,随后几年在中国南方杂色鲍养殖区广泛传播(Wang et al, 2004)。病鲍主要表现为摄食量减少、活力下降和黏液分泌增多等非典型症状,出现症状3~ 7 d后即发生大规模死亡(宋振荣等, 2000)。这也是鲍首次因病毒感染发生急性死亡的案例,从出现症状到大规模死亡仅3~5 d,致死率高达95%以上(Wang et al, 2004)。流行病学调查结果显示,该疫病只发生在南方水温较低的季节,因此被称为鲍低温病毒病。但当时因技术所限,未能进一步鉴定该病毒病原,该疫病在我国也被称为鲍病毒性死亡病。2003和2005年,台湾地区养殖杂色鲍和澳大利亚的黑唇鲍(Haliotis rubra)、绿唇鲍(Haliotis laevigata)及其杂交种,分别发生类似的疱疹病毒引起的急性病毒性大规模死亡(Chang et al, 2005; Hooper et al, 2007)。病鲍表现的主要病理特征是腹足神经节和中枢神经组织炎症和细胞浸润,因此,该病又被称为鲍病毒性神经炎(Abalone viral ganglioneuritis, AVG)(Hooper et al, 2007)。对感染澳大利亚鲍的疱疹病毒粒子进行基因组序列测定和分析,结果显示,AVG病原为一种新疱疹病毒,与OsHV-1的亲缘关系较近,ICTV将该病毒命名为鲍疱疹病毒1 (Haliotid herpesvirus 1, HaHV-1)。

根据最近开展的回溯性研究,中国南方1999年起发生的鲍低温病毒病病原,与台湾地区和澳大利亚发生的AVG病原为同一种病毒,即鲍疱疹病毒(Bai et al, 2019a; Wei et al, 2018)。由于HaHV-1的高传染性和致死率,其在中国南方反复发作几年后,目前中国杂色鲍养殖产业几近灭绝。截止目前,只在以上3个国家和地区发现HaHV-1感染案例,其易感物种除了以上提到的几种外,还有棕唇鲍(Haliotis conicopora)。研究结果还证实,新西兰黑金鲍(Haliotis iris)与皱纹盘鲍(Haliotis discus hannai)对HaHV-1不敏感(Bai et al, 2019a; Corbeil et al, 2017)。

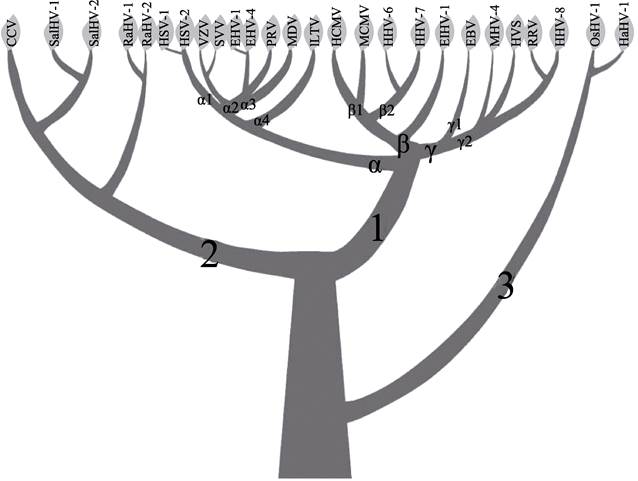

2 软体动物疱疹病毒的基本特征与株系分化 2.1 软体动物疱疹病毒的分类地位软体动物疱疹病毒与已知感染陆生和水生脊椎动物的疱疹病毒亲缘关系较远。2011年,ICTV在其发布的第九次报告中,将原疱疹病毒科提升为疱疹病毒目(Herpesvirales),重新设置3个疱疹病毒科,其成员分别感染陆生脊椎动物、水生脊椎动物和无脊椎动物(Davison et al, 2002)(图 2)。其中,软体动物疱疹病毒科(Malacoherpesviridae)目前由2个属(Ostreavirus和Aurivirus)组成,每个属包含1个病毒种,分别为OsHV-1和HaHV-1 (Minson et al, 2011)。

|

图 2 疱疹病毒目系统发育树拓扑结构示意图(获ELSEVIER出版集团授权刊载) Fig.2 A sketch of the herpesvirus evolutionary tree (Reprinted with permission from Elsevier) 1:陆生脊椎动物疱疹病毒; 2:水生脊椎动物疱疹病毒; 3:软体动物疱疹病毒 1: Herpesviridae, 2: Alloherpesviridae, 3: Malacoherpesviridae |

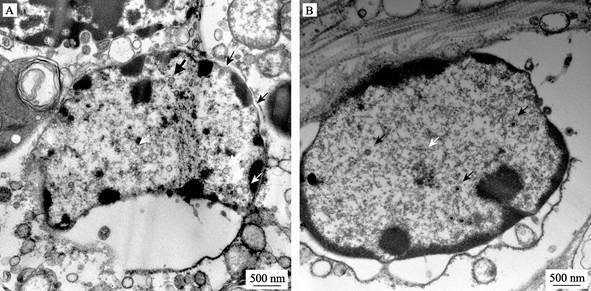

软体动物疱疹病毒核衣壳具有疱疹病毒典型的正二十面体结构,核衣壳内是以双链DNA为核心的遗传物质(图 3)。核衣壳在细胞核内完成装配,并被运出细胞核,在高尔基体及释放到胞外过程中完成被膜(Tegument)和囊膜的装配。有关OsHV-1形态结构的电镜观测报道相对较多,涉及多个物种,其核衣壳直径在71~111 nm之间,装配好的病毒颗粒直径为106~153 nm (图 3A) (Arzul et al, 2001a; Bai et al, 2016; Hine et al, 1998; Renault et al, 2000a)。HaHV-1相关的研究报道较少,其核衣壳直径约为100 nm (图 3B),仅有1例报道观察到处于细胞外、完成装配的病毒粒子,直径约为165 nm (Corbeil et al, 2012)。仅凭电镜下病毒的形态特征不能区分OsHV-1和HaHV-1。

|

图 3 OsHV-1感染魁蚶(A)和HaHV-1感染杂色鲍(B)细胞核中观察到的疱疹样病毒 Fig.3 Viral particles identified in the nuclei of OsHV-1 infected S. broughtonii (A) and HaHV-1 infected H. diversicolor supertexta (B) 白箭头:空衣壳; 黑箭头:核衣壳 White arrows: Empty capsids; Black arrows: Nucleocapsid |

OsHV-1和HaHV-1基因组大小相似,约为210 kb,但其GC含量不同,分别为38.7%和46.8% (Davison et al, 2005; Savin et al, 2010)。疱疹病毒的基因组并不是简单的单一序列,而是由多个直接或反向重复序列与数个单一序列按不同模式间隔排列组成。根据排列模式的不同,可以把疱疹病毒基因组分为6种类型(Roizman et al, 2001)。OsHV-1的结构模式可以概括为TRL-UL-IRL-X-IRS-US-TRS,其中UL和US是单一序列,在参考基因组中的长度分别为167843和3370 bp,TRL/IRL和TRS/IRS是2对反向重复序列,长度分别为9774和7584 bp,X也是单一序列,长度为1510 bp (Davison et al, 2005)。利用高通量测序技术对OsHV-1微变株(OsHV-1μvar)的深度测序结果表明,X区的测序深度是OsHV-1基因组其他区域的2倍,推测OsHV-1微变株基因组包含双拷贝的X区,另一个位于基因组末端。因此,微变株的基因组结构可能是TRL-UL-IRL-X-IRS-US-TRS-X’或X’-TRL-UL-IRL- X-IRS-US-TRS (Abbadi et al, 2018; Burioli et al, 2017)。不同变异株基因组结构单元的长度可能有差异,但其结构模式相似(Ren et al, 2013; Xia et al, 2015)。预测OsHV-1基因组编码124个开放阅读框(Open reading frame, ORF)(Davison et al, 2005)。HaHV-1的结构模式相对简单,可以概括为TRL-UL-IRL-IRS-US-TRS,预测编码110个ORFs (数据未发表)。

2.3 软体动物疱疹病毒的变异与株系分化软体动物疱疹病毒在自然界存在多种变异株,它们的组成和比例不断演化,以适应不断变化的生态环境。目前,研究较多的OsHV-1变异株有参考株(Davison et al, 2005)、扇贝急性病毒性坏死病毒(AVNV)、微变株(OsHV-1μvar)和魁蚶株(OsHV-1-SB); 其中,参考株和微变株最早都发现于长牡蛎养殖业发达的法国(Davison et al, 2005; Segarra et al, 2010),AVNV和OsHV-1-SB分别来自中国养殖栉孔扇贝和魁蚶(Bai et al, 2016; Ren et al, 2013)。已公布的OsHV-1 7个变异株基因组序列相似性为93.5% (Bai et al, 2019b),而单纯疱疹病毒2 (Herpes simplex virus 2)与单纯疱疹病毒1 (Herpes simplex virus 1)的这一比例分别为99.6%和96.8% (Norberg et al, 2007; Szpara et al, 2014)。OsHV-1不同变异株间相对较低的序列相似度,可能与其和不同宿主长期协同进化过程中发生较强的株系分化有关。

基于不同OsHV-1变异株基因组序列构建的系统发育树显示,各变异株以其宿主不同(栉孔扇贝、长牡蛎和魁蚶)分为3个支系,说明宿主范围在该病毒系统分化过程中占主导地位(Bai et al, 2019b)。在宿主为长牡蛎的病毒支系中,在法国海区先后发现的OsHV-1参考株和微变株之间呈姊妹支关系,而不是祖先与后代关系(Segarra et al, 2010; Bai et al, 2019b)。根据病毒基因组高变异位点序列,多个研究团队分析了本国或部分区域内OsHV-1不同变异株的演化和变异规律(Bai et al, 2015; Batista et al, 2015; Mineur et al, 2015; Renault et al, 2012; Shimahara et al, 2012)。对中国2001~2013年间27个海区贝类样品OsHV-1的感染情况、C2/C6位点序列变异、病毒株系分化及其时空分布规律进行分析,发现中国存在多达24种变异株,OsHV-1种群间存在因地理隔离和时间推移产生的种群分化(Bai et al, 2015)。基于不同地区变异株C2/C6位点多态性差异等分析结果,Mineur等(2015)推测,OsHV-1起源于亚洲地区,伴随长牡蛎引种传播到全球各地,但目前这一假说尚未得到更多数据的支撑。目前,OsHV-1的起源和全球传播过程还不清楚,现有结果表明,OsHV-1是一个古老的疱疹病毒支系,已与其天然宿主经过长期的协同演化过程。自然界存在多个OsHV-1变异株,近年来在贝类高密度养殖、脱离原有生境等的应激压力下,OsHV-1病害相继发生。

法国开展的OsHV-1分子流行病学监测结果显示,OsHV-1新变异株的不断出现给贝类养殖产业造成严重威胁。例如,OsHV-1最初在法国暴发时致病力较弱,虽然造成的长牡蛎幼虫死亡曾引起苗种短缺,给当地养殖业造成不利影响,但法国长牡蛎年产量仅小幅下挫,从1991年的12.9万t跌至2007的11.1万t (FAO渔业统计年鉴)。2008年,法国开始大范围流行致病力更强的微变株(OsHV-1μvar),主要引起海区养殖稚贝和幼贝的大规模死亡,导致近年来法国长牡蛎年产量跌至6.4万t (FAO渔业统计年鉴)。这些结果提示,未来应加强OsHV-1的分子流行病学监测,及时评估和应对新变异株对中国贝类养殖业造成的威胁。

HaHV-1株系分化和分子流行病学的相关研究还很欠缺,根据其地理分布分为中国大陆株、台湾株和澳大利亚株,它们基因组序列间的相似度为91.5% (Bai et al, 2019c; Chen et al, 2016; Savin et al, 2010)。已知的HaHV-1易感宿主都来自Haliotis属,均引起宿主的急性感染和死亡。然而,2009年起,台湾地区发生疱疹病毒引起的杂色鲍慢性死亡案例,死亡可从早春一直持续到秋季,累计死亡率达80%左右,成为台湾鲍养殖业面临的主要疫病(Chen et al, 2016)。基于HaHV-1基因组设计的20对引物,均不能从慢性死亡鲍样本中扩增出条带,推测引起鲍慢性死亡的疱疹病毒与HaHV-1基因组序列相似度很低,其与HaHV-1的关系还有待进一步研究(Chen et al, 2016)。

3 软体动物疱疹病毒感染的致病特征 3.1 病理特征OsHV-1感染的病理变化广泛分布于各主要器官的结缔组织,如外套膜、鳃、肝胰腺和生殖腺等,病变组织内常伴有以染色质边集和核固缩为特征的异常细胞核(Renault et al, 2000a; Segarra et al, 2016)。常见的受感染细胞类型有成纤维细胞、血淋巴细胞,偶尔也能观察到感染的神经细胞和肌细胞(Lipart et al, 2002; Segarra et al, 2016; Xin et al, 2018)。利用原位杂交技术在发病牡蛎生殖腺中还观察到被病毒DNA探针标记的感染细胞,部分细胞鉴定为卵母细胞(Corbeil et al, 2015),从分离的卵细胞和精细胞中检测到病毒DNA,推测OsHV-1存在垂直传播的可能性(López-Sanmartín et al, 2016b)。另外,在部分欧洲牡蛎(Comps et al, 1993)和新西兰牡蛎(Hine et al, 1997)感染案例中,观察到核内Cowdry type A型包涵体,但未在包括长牡蛎在内的其他贝类中发现包涵体(Arzul et al, 2017)。

HaHV-1澳大利亚株和台湾株感染的组织病变集中在中枢神经组织,而引起鲍慢性死亡的疱疹病毒主要感染血淋巴细胞,并造成结缔组织损伤和血细胞浸润(Chen et al, 2016)。Bai等(2020)基于组织病理和原位杂交的分析结果显示,HaHV-1大陆株感染不仅引起杂色鲍足神经节和中枢神经组织病变,在外周神经组织、感染后期的外套膜、肝胰腺等器官的结缔组织也出现病变和病毒探针标记的感染细胞; 利用透射电镜,还在感染的鲍血淋巴细胞中观察到疱疹样病毒粒子。目前,HaHV-1中国大陆与台湾株、澳大利亚株组织亲嗜性差异的原因还不清楚,我们推测与宿主和病原如下两方面的差异相关,一是由HaHV-1不同地理种群株系分化导致的致病性差异,二是宿主品种或品系差异引起组织器官易感性不同。

3.2 疫病发生和流行规律温度是影响OsHV-1与HaHV-1感染强度,发病与否和危害程度的关键环境因子(Arzul et al, 2017),但2种病毒对温度的响应模式相反:OsHV-1感染在水温上升到某个阈值的高温季节发病,HaHV-1感染在水温下降到某个阈值的低温季节发病。OsHV-1感染发病的温度阈值大小受变异株和宿主物种的共同影响,如OsHV-1参考株(2008年之前)感染长牡蛎在21.5℃~26.8℃之间时发病(Sauvage et al, 2009),OsHV-1μvar (2008年之后)感染长牡蛎在15.5℃~ 23.8℃之间时发病(Pernet et al, 2012; Petton et al, 2015),栉孔扇贝在23℃以上时发病(宋微波等, 2001; 王崇明等, 2002),魁蚶在14℃以上时发病(Xin et al, 2020)。不同的海区环境(如维度、理化因子等)也会影响温度阈值。近年来,法国及欧洲养殖长牡蛎发病的温度阈值一般为16℃,而澳大利亚养殖长牡蛎发病的温度阈值一般是21℃ (de Kantzow et al, 2019)。除温度之外,其他环境因子也对OsHV-1疫病产生影响,如盐度(Fuhrmann et al, 2018、2016)、环境微生物(Azema et al, 2016; Pathirana et al, 2019)、饵料丰度(Pernet et al, 2019b)和pH值(Fuhrmann et al, 2019)等。但这类环境因子对OsHV-1疫病的影响效应不如温度直接和明确。温度主要通过控制病毒是否进入指数复制期发挥作用,其效应更加明显和可预测; 其他环境因子主要通过与宿主间复杂的相互作用发挥作用,其对疫病发生和进程的影响表现出明显的地区特异性(Fleury et al, 2020; Pernet et al, 2019b)。

Oden等(2011)对病毒感染长牡蛎的研究结果显示,OsHV-1感染是否引发宿主的发病和死亡主要取决于病毒在宿主体内的拷贝数,如果病毒拷贝数超过8.8×103个/mg组织,则会发病和死亡,否则通常以无症状感染的形式长期存在。除栉孔扇贝、魁蚶、毛蚶和新西兰牡蛎之外,OsHV-1感染引发的病亡主要发生于幼虫和稚贝阶段。对长牡蛎、福建牡蛎等的流行病学监测结果显示,其成贝往往不表现任何临床症状,体内病毒感染量也多在103个/mg组织以下,这些无症状的成贝就成为OsHV-1在自然界中的天然“蓄水池”,且存在将病毒经垂直传播给下一代的可能(Barbosa-Solomieu et al, 2005; López-Sanmartín et al, 2016b)。目前,尚无证据显示HaHV-1感染也表现类似的对宿主发育阶段的偏好性。

Paul-Pont等(2013b)对澳大利亚Botany湾OsHV-1致死病例的空间分布规律研究显示,牡蛎发病呈聚集性“斑块”状分布,斑块大小在几个阀架至数公里不等,斑块的空间分布主要与牡蛎月龄和湾内洋流方向相关。Paul-Pont等推测,OsHV-1的水平传播方式主要是粘附于水中的浮游生物,依赖洋流传播。

4 软体动物疱疹病毒诊断方法 4.1 传统诊断技术组织病理和透射电镜检测作为传统的贝类疫病诊断技术,已被应用到软体动物疱疹病毒的诊断工作中。OsHV-1感染的诊断可以取外套膜、肝胰腺和鳃等组织器官,HaHV-1感染诊断须首先小心对鲍腹足进行纵切,而后取足神经节进行检测(Mark et al, 2016)。欧盟贝类病害参考实验室提供了详细的样本处理、检测操作规程。在光镜下观察,若双壳贝类样本结缔组织出现大量细胞浸润,其中的成纤维细胞和血细胞呈现染色质边集或核浓缩等细胞病变,则为疑似OsHV-1感染。若鲍样本足神经节和中枢神经组织出现病变,则为疑似HaHV-1感染。组织病理变化不是特异性的,因此不能用于确诊。透射电镜下,细胞核内观察到疱疹样病毒粒子,可判定检测结果为阳性; 但这种检测不是种特异性的,需要结合分子生物学技术,做出最后确诊。

4.2 现代诊断技术 4.2.1 基于PCR法的诊断技术聚合酶链反应(PCR)诊断技术以其高敏感性、高特异性和快速简便的优点,已成为包括贝类在内众多水产动物病原常用的检测技术。法国学者首先设计了OsHV-1巢式PCR检测用引物(A3/A4和A5/A6)(Renault et al, 2000b),但很快被检测灵敏度更高的普通PCR检测引物(C2/C6)所取代(Renault et al, 2001a)。随后,多种OsHV-1检测用PCR引物相继报道,但多数引物的检测灵敏度和特异性未得到充分验证,C2/C6仍是目前应用最广泛的普通PCR引物(Batista et al, 2007)。实时定量PCR检测凭借其可对感染量进行精确测定的优势,近年来越来越多的被应用到涉及OsHV-1检测的各种研究项目中。目前,常用的OsHV-1实时定量PCR检测方法有2种,分别是使用C9/C10的SYBR Green法和使用OsHV1BF/B4引物及对应探针的TaqMan探针法(Martenot et al, 2010; Pepin et al, 2008)。对HaHV-1检测方法的研究相对较少,但也有比较成熟的普通PCR和实时定量PCR检测方法可供使用(Mark et al, 2016)。

4.2.2 原位杂交诊断技术原位杂交技术具有细胞定位能力准确、特异性好和敏感度高等优点。OsHV-1和HaHV-1原位杂交检测均使用地高辛标记探针。OsHV-1检测有3种大小相似的探针可供选择,分别由3对引物(A5/A6、C1/C6和C2/C6)扩增产生(Corbeil et al, 2015; Lipart et al, 2002); HaHV-1检测一般使用ORF66F/R引物合成探针(Mark et al, 2016)。另外,Corbeil等(2015)开发了一种可以检测OsHV-1 3个病毒RNA(ORF7、25和87)原位表达情况的探针杂交技术。

4.2.3 其他分子诊断技术除了上述实验室常用的诊断技术外,中国研究人员还基于环介导等温扩增(Loop-mediated isothermal amplification, LAMP)和荧光定量重组酶聚合酶扩增(Quantitative recombinase polymerase amplification, qRPA)技术,开发了OsHV-1和HaHV-1的检测方法(Chen et al, 2014; Gao et al, 2018a、b; Ren et al, 2010),这些检测技术具有更加简便、快捷、适合现场应用的优点。

5 软体动物疱疹病毒病的防控贝类养殖多在开放式海区进行,很多涉及药物的预防和治疗措施无法施展,给包括软体动物疱疹病毒病在内多种贝类疫病的防控带来困难。为此,针对软体动物疱疹病毒,特别是OsHV-1的生物学特性、发病规律、抗病品系选育等方面开展了大量研究,研发相关防控措施(Barbosa-Solomieu et al, 2015)。但HaHV-1的相关研究还较少,对该疫病的防控主要依靠划定病毒污染区、限制鲍及相关物品的跨区流动等基本生物安保措施(Mark et al, 2016)。本节主要介绍OsHV-1相关防控措施的研究进展。

5.1 OsHV-1生物学特征及室内消杀措施贝类的室内养殖一般发生在育苗阶段,OsHV-1流行早期(2008年之前)的多数案例是育苗场幼虫的死亡。对OsHV-1生物学特征的研究结果显示,在室内20℃情况下,OsHV-1可在海水和死亡牡蛎内脏团中分别存活2 d和7 d,并仍保持感染能力,给病毒的彻底消杀工作造成一定困难(Hick et al, 2016)。有利的一点是,OsHV-1作为一种具有脂质囊膜的病毒,在水产养殖环境中属于比较容易杀灭的病原体。高温(50℃,5 min)、化学消毒剂(如10%福尔马林,30 min)、臭氧和紫外线对该病毒均有较好的杀灭作用(Evans et al, 2016; Hick et al, 2016)。由于成贝往往处于隐性感染状态,有可能作为传染源被引入育苗场。为了预防此类事件的发生,研究人员建议对进场前的成贝进行热应激(水温升至21℃) 2~3周,以便使成贝体内潜伏感染的OsHV-1激活和复制,而后进行PCR检测,排除潜伏感染成贝带来的威胁(Hine et al, 1997; Pernet et al, 2015)。

我国部分鲜活贝类上市或出口前需在室内暂养数周,此时养殖密度高,容易暴发流行病和大规模死亡。根据软体动物疱疹病毒感染的发生受温度调控这一特点,可通过控制水温预防疫病的发生。实验结果和生产实践均表明,水温控制在10℃及以下可有效防止魁蚶暂养阶段发生OsHV-1感染。但值得注意的是,不同物种感染软体动物疱疹病毒后发病的温度阈值可能不同,需要通过系统的实验确定。

5.2 开放海区OsHV-1病害的综合防控 5.2.1 养殖措施的改善在法国地中海沿岸,相对开放海区OsHV-1疫病死亡率低于湾内,插桩式养殖低于吊篮式养殖(Pernet et al, 2012)。澳大利亚和法国开展的研究均表明,增加潮间带养殖阀架的高度(30~60 cm)可有效降低成贝的OsHV-1感染率、感染强度和死亡率(Paul-Pont et al, 2013a)。引起这一现象的机制尚不清楚,推测可能是增加养殖阀架高度后,减少了牡蛎浸水和接触病毒的时间(Paul-Pont et al, 2013a; Petton et al, 2015)。但这项措施也会减少牡蛎摄食时间,从而导致生长缓慢、甚至应激反应(Pernet et al, 2019a)。因此,在水文环境复杂、养殖方式多样的开放式海区,养殖措施的改良应充分考虑苗种来源(人工苗或野生苗)、遗传背景、繁殖周期和月龄等因素(Evans et al, 2019; Ugalde et al, 2018); 很难形成一套适合所有海区的OsHV-1防控技术规程,也很难依靠单一技术实现OsHV-1病害的有效防控(Fleury et al, 2020)。遵循“因地制宜、多管齐下”的策略,才能通过养殖措施的优化缓解OsHV-1给贝类养殖产业带来的危害。例如,西班牙埃布罗河三角洲地区受OsHV-1疫情的影响,长牡蛎年产量从2006年的800 t缩减到2011年的138 t (Carrasco et al, 2017)。当地通过改良生产周期、避开危险期投放稚贝苗种,控制投苗规格,降低养殖密度和优化生产管理方法等一系列措施,使当地牡蛎养成期死亡率从2015年之前的约80%,下降到2015年及之后的2%~7.5% (Carrasco et al, 2017)。

5.2.2 抗病品系选育对长牡蛎和魁蚶的研究表明,天然存在对OsHV-1不敏感的家系,这为抗病品系选育提供了自然资源(Bai et al, 2017; Dégremont et al, 2005)。我们开展的感染实验和生产数据显示,韩国来源的魁蚶对OsHV-1普遍不敏感,近年来多被中国魁蚶育苗企业选为种贝。对15个长牡蛎家系的感染实验结果显示,人工感染14 d后的成活率各不相同,范围在0~97.4%之间(de Lorgeril et al, 2018)。进一步分析发现,长牡蛎表现出较高的抗OsHV-1加性遗传变异,遗传力大小在0.12~0.63之间(Azema et al, 2015; Camara et al, 2017; Dégremont et al, 2015)。目前,法国、英国和新西兰等均已启动各自的抗OsHV-1长牡蛎选育项目,法国通过对不同长牡蛎家系连续4代的大规模抗病毒选育,使3~6月龄牡蛎的成活率提高7%~63% (Dégremont et al, 2015)。

6 结论与展望中国的贝类养殖规模大、种类全,目前在养的贝类约80种,发挥着重要的食物供给和生态服务功能(唐启升等, 2016)。进入21世纪,贝类的高密度养殖模式和人工苗种繁育技术得以广泛推广(唐启升等, 2013; 阙华勇等, 2016),在推动养殖产量不断提升的同时,也导致传染性病害频繁发生,使中国贝类养殖业蒙受巨大经济损失。已开展的软体动物疱疹病毒相关研究使我们对贝类病毒病有了更深入的认识,但仍存在很多知识盲区,如病毒结构蛋白的组成和功能、入侵和致病机制等对病毒病防控至关重要的基础科学问题(张奇亚等, 2014); 变异株鉴别诊断及其在中国海区的分布范围和流行规律等,与疫病有效防控息息相关的基本信息也尚未掌握。

当前,中国贝类养殖业尚缺乏生物安保(Biosecurity)理念指导下的疫病风险管理和应对策略(黄倢等, 2016)。在此背景下的苗种跨区转运、南北接力养殖等,都有可能导致病原微生物的传播,威胁贝类养殖业的健康发展。在贝类主产区建立贝类疫病预警系统(宋林生, 2020),引入生物安保概念,提高生物安保意识,贯彻和落实生物安保指导下的健康养殖理念(黄倢等, 2016),才能实现软体动物疱疹病毒等贝类疫病的有效防控。

Abbadi M, Zamperin G, Gastaldelli M, et al. Identification of a newly described OsHV-1µvar from the North Adriatic Sea (Italy). Journal of General Virology, 2018, 99(5): 693-703 DOI:10.1099/jgv.0.001042 |

Arzul I, Corbeil S, Morga B, et al. Viruses infecting marine molluscs. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2017, 147: 118-135 DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2017.01.009 |

Arzul I, Nicolas JL, Davison AJ, et al. French scallops:A new host for Ostreid herpesvirus-1. Virology, 2001a, 290(2): 342-349 DOI:10.1006/viro.2001.1186 |

Arzul I, Renault T, Lipart C, et al. Evidence for interspecies transmission of oyster herpesvirus in marine bivalves. Journal of General Virology, 2001b, 82(4): 865-870 DOI:10.1099/0022-1317-82-4-865 |

Azéma P, Travers MA, Benabdelmouna A, et al. Single or dual experimental infections with Vibrio aestuarianus and OsHV-1 in diploid and triploid Crassostrea gigas at the spat, juvenile and adult stages. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2016, 139: 92-101 DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2016.08.002 |

Azéma P, Travers MA, De Lorgeril J, et al. Can selection for resistance to OsHV-1 infection modify susceptibility to Vibrio aestuarianus infection in Crassostrea gigas?First insights from experimental challenges using primary and successive exposures. Veterinary Research, 2015, 46: 139 DOI:10.1186/s13567-015-0282-0 |

Bai CM, Gao WH, Wang CM, et al. Identification and characterization of Ostreid herpesvirus 1 associated with massive mortalities of Scapharca broughtonii broodstocks in China. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 2016, 118(1): 65-75 DOI:10.3354/dao02958 |

Bai CM, Li YN, Chang PH, et al. In situ hybridization revealed wide distribution of Haliotid herpesvirus 1 in infected small abalone, Haliotis diversicolor supertexta. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2020, 173: 107356 DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2020.107356 |

Bai CM, Li YN, Chang PH, et al. Susceptibility of two abalone species, Haliotis diversicolor supertexta and Haliotis discus hannai, to Haliotid herpesvirus 1 infection. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2019a, 160: 26-32 DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2018.11.008 |

Bai CM, Morga B, Rosani U, et al. Long-range PCR and high-throughput sequencing of Ostreid herpesvirus 1 indicate high genetic diversity and complex evolution process. Virology, 2019b, 526: 81-90 DOI:10.1016/j.virol.2018.09.026 |

Bai CM, Rosani U, Li YN, et al. RNA-seq of HaHV-1-infected abalones reveals a common transcriptional signature of Malacoherpesviruses. Scientific Reports, 2019c, 9(1): 938 DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-36433-w |

Bai CM, Wang CM, Xia JY, et al. Emerging and endemic types of Ostreid herpesvirus 1 were detected in bivalves in China. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2015, 124: 98-106 DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2014.11.007 |

Bai CM, Wang QC, Morga B, et al. Experimental infection of adult Scapharca broughtonii with Ostreid herpesvirus SB strain. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2017, 143: 79-82 DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2016.12.001 |

Barbosa-Solomieu V, Dégremont L, Vázquez-Juárez R, et al. Ostreid Herpesvirus 1(OsHV-1) detection among three successive generations of Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas). Virus Research, 2005, 107(1): 47-56 DOI:10.1016/j.virusres.2004.06.012 |

Barbosa-Solomieu V, Renault T, Travers MA. Mass mortality in bivalves and the intricate case of the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2015, 131: 2-10 DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2015.07.011 |

Batista FM, Arzul I, Pepin JF, et al. Detection of Ostreid herpesvirus 1 DNA by PCR in bivalve molluscs:A critical review. Journal of Virological Methods, 2007, 139(1): 1-11 DOI:10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.09.005 |

Batista FM, López-Sanmartín M, Grade A, et al. Sequence variation in Ostreid herpesvirus 1 microvar isolates detected in dying and asymptomatic Crassostrea angulata adults in the Iberian Peninsula:Insights into viral origin and spread. Aquaculture, 2015, 435: 43-51 DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2014.09.016 |

Burioli EAV, Prearo M, Houssin M. Complete genome sequence of Ostreid herpesvirus type 1 μVar isolated during mortality events in the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas in France and Ireland. Virology, 2017, 509: 239-251 DOI:10.1016/j.virol.2017.06.027 |

Camara MD, Yen S, Kaspar HF, et al. Assessment of heat shock and laboratory virus challenges to selectively breed for Ostreid herpesvirus 1(OsHV-1) resistance in the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Aquaculture, 2017, 469: 50-58 DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2016.11.031 |

Carrasco N, Gairin I, Pérez J, et al. A production calendar based on water temperature, spat size, and husbandry practices reduce OsHV-1 μvar impact on cultured pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas in the Ebro Delta (Catalonia), Mediterranean coast of Spain. Frontiers in Physiology, 2017, 8: 125 |

Chang PH, Kuo ST, Lai SH, et al. Herpes-like virus infection causing mortality of cultured abalone Haliotis diversicolor supertexta in Taiwan. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 2005, 65(1): 23-27 |

Chen IW, Chang PH, Chen MS, et al. Exploring the chronic mortality affecting abalones in Taiwan:Differentiation of abalone herpesvirus-associated acute infection from chronic mortality by PCR and in situ hybridization and histopathology. Taiwan Veterinary Journal, 2016, 42(1): 1-9 DOI:10.1142/S1682648515500237 |

Chen MH, Kuo ST, Renault T, et al. The development of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for rapid and sensitive detection of abalone herpesvirus DNA. Journal of Virological Methods, 2014, 197: 199-203 |

Comps M, Cochennec N. A herpes-like virus from the European oyster Ostrea edulis L. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 1993, 62(2): 201-203 DOI:10.1006/jipa.1993.1098 |

Corbeil S, Faury N, Segarra A, et al. Development of an in situ hybridization assay for the detection of Ostreid herpesvirus type 1 mRNAs in the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas. Journal of Virological Methods, 2015, 211: 43-50 DOI:10.1016/j.jviromet.2014.10.007 |

Corbeil S, McColl KA, Williams LM, et al. Abalone viral ganglioneuritis:Establishment and use of an experimental immersion challenge system for the study of abalone herpes virus infections in Australian abalone. Virus Research, 2012, 165(2): 207-213 DOI:10.1016/j.virusres.2012.02.017 |

Corbeil S, McColl KA, Williams LM, et al. Innate resistance of New Zealand paua to abalone viral ganglioneuritis. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2017, 146: 31-35 DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2017.04.005 |

Crane MSJ, McColl K, Cowley J, et al. Abalone herpesvirus.In:Liu D (ed).Molecular detection of animal viral pathogens. CRC Press, 2016, 807-815 |

Davison AJ, Trus BL, Cheng N, et al. A novel class of herpesvirus with bivalve hosts. Journal of General Virology, 2005, 86(1): 41-53 DOI:10.1099/vir.0.80382-0 |

Davison AJ. Evolution of the herpesviruses. Veterinary Microbiology, 2002, 86(1-2): 69-88 DOI:10.1016/S0378-1135(01)00492-8 |

de Kantzow M, Whittington RJ, Hick P. Prior exposure to Ostreid herpesvirus 1(OsHV-1) at 18℃ is associated with improved survival of juvenile Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas) following challenge at 22℃. Aquaculture, 2019, 507: 443-450 DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.04.035 |

de Lorgeril J, Lucasson A, Petton B, et al. Immune-suppression by OsHV-1 viral infection causes fatal bacteraemia in Pacific oysters. Nature Communications, 2018, 9(1): 4215 DOI:10.1038/s41467-018-06659-3 |

Dégremont L, Bédier E, Soletchnik P, et al. Relative importance of family, site, and field placement timing on survival, growth, and yield of hatchery-produced Pacific oyster spat (Crassostrea gigas). Aquaculture, 2005, 249(1-4): 213-229 DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2005.03.046 |

Dégremont L, Garcia C, Allen Jr SK. Genetic improvement for disease resistance in oysters:A review. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2015, 131: 226-241 DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2015.05.010 |

Evans O, Hick P, Whittington RJ. Distribution of Ostreid herpesvirus-1 (OsHV-1) microvariant in seawater in a recirculating aquaculture system. Aquaculture, 2016, 458: 21-28 DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2016.02.027 |

Evans O, Kan JZF, Pathirana E, et al. Effect of emersion on the mortality of Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas) infected with Ostreid herpesvirus-1(OsHV-1). Aquaculture, 2019, 505: 157-166 DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.02.041 |

Farley CA, Banfield WG, Kasnic Jr. G, et al. Oyster herpes-type virus.Science, 1972, 178(4062): 759-760 |

Fleury E, Barbier P, Petton B, et al. Latitudinal drivers of oyster mortality:Deciphering host, pathogen and environmental risk factors. Scientific Reports, 2020, 10(1): 7264 DOI:10.1038/s41598-020-64086-1 |

Fuhrmann M, Delisle L, Petton B, et al. Metabolism of the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas, is influenced by salinity and modulates survival to the Ostreid herpesvirus OsHV-1. Biology Open, 2018, 7(2): bio028134 DOI:10.1242/bio.028134 |

Fuhrmann M, Petton B, Quillien V, et al. Salinity influences disease-induced mortality of the oyster Crassostrea gigas and infectivity of the Ostreid herpesvirus 1(OsHV-1). Aquaculture Environment Interactions, 2016, 8: 543-552 DOI:10.3354/aei00197 |

Fuhrmann M, Richard G, Quéré C, et al. Low pH reduced survival of the oyster Crassostrea gigas exposed to the Ostreid herpesvirus 1 by altering the metabolic response of the host. Aquaculture, 2019, 503: 167-174 DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.12.052 |

Gao F, Jiang JZ, Wang JY, et al. Real-time isothermal detection of abalone herpes-like virus and red-spotted grouper nervous necrosis virus using recombinase polymerase amplification. Journal of Virological Methods, 2018a, 251: 92-98 DOI:10.1016/j.jviromet.2017.09.024 |

Gao F, Jiang JZ, Wang JY, et al. Real-time quantitative isothermal detection of Ostreid herpesvirus-1 DNA in Scapharca subcrenata using recombinase polymerase amplification. Journal of Virological Methods, 2018b, 255: 71-75 DOI:10.1016/j.jviromet.2018.02.007 |

Guo X, Ford SE. Infectious diseases of marine molluscs and host responses as revealed by genomic tools. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London.Series B, Biological Sciences, 2016, 371(1689): 20150206 DOI:10.1098/rstb.2015.0206 |

Hick P, Evans O, Looi R, et al. Stability of Ostreid herpesvirus-1(OsHV-1) and assessment of disinfection of seawater and oyster tissues using a bioassay. Aquaculture, 2016, 450: 412-421 DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2015.08.025 |

Hine PM, Thorne T. Replication of herpes-like viruses in haemocytes of adult flat oysters Ostrea angasi an ultrastructural study. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 1997, 29(3): 189-196 |

Hine PM, Wesnay B, Basant P. Replication of a herpes-like virus in larvae of the flat oyster Tiostrea chilensis at ambient temperatures. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 1998, 32(3): 161-171 |

Hine PM, Wesney B, Hay B. Herpesviruses associated with mortalities among hatchery-reared larval Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 1992, 12(2): 135-142 |

Hooper C, Hardy-Smith P, Handlinger J. Ganglioneuritis causing high mortalities in farmed Australian abalone (Haliotis laevigata and Haliotis rubra). Australian Veterinary Journal, 2007, 85(5): 188-193 DOI:10.1111/j.1751-0813.2007.00155.x |

Huang J, Zeng LB, Dong X, et al. Trend analysis and policy recommendation on aquatic biosecurity in China. Engineering Sciences, 2016, 18(3): 15-21 [黄倢, 曾令兵, 董宣, 等. 水产生物安保发展趋势与政策建议. 中国工程科学, 2016, 18(3): 15-21 DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1009-1742.2016.03.004] |

Hwang JY, Park JJ, Yu HJ, et al. Ostreid herpesvirus 1 infection in farmed Pacific oyster larvae Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg) in Korea. Journal of Fish Diseases, 2013, 36(11): 969-972 DOI:10.1111/jfd.12093 |

Kim HJ, Jun JW, Giri SS, et al. Mass mortality in Korean bay scallop (Argopecten irradians) associated with Ostreid Herpesvirus-1 μVar. Transboundary Emerging Diseases, 2019, 66(4): 1442-1448 |

Lipart C, Renault T. Herpes-like virus detection in infected Crassostrea gigas spat using DIG-labelled probes. Journal of Virological Methods, 2002, 101(1-2): 1-10 DOI:10.1016/S0166-0934(01)00413-X |

López-Sanmartín M, López-Fernández JR, Cunha ME, et al. Ostreid herpesvirus in wild oysters from the Huelva coast (SW Spain). Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 2016a, 120(3): 231-240 DOI:10.3354/dao03031 |

López-Sanmartín M, Power DM, de la Herrán R, et al. Evidence of vertical transmission of Ostreid herpesvirus 1 in the Portuguese oyster Crassostrea angulata. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2016b, 140: 39-41 DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2016.08.012 |

Martenot C, Oden E, Travaille E, et al. Comparison of two real-time PCR methods for detection of Ostreid herpesvirus 1 in the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Journal of Virological Methods, 2010, 170(1-2): 86-89 DOI:10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.09.003 |

Mineur F, Provan J, Arnott G. Phylogeographical analyses of shellfish viruses:inferring a geographical origin for Ostreid herpesviruses OsHV-1(Malacoherpesviridae). Marine Biology, 2015, 162(1): 181-192 DOI:10.1007/s00227-014-2566-8 |

Minson A, Davison A, Eberle R, et al. Family herpesviridae.In:Andrew M.Q.King, Michael J.Adams, Eric B.Carstens (eds).Virus Taxonomy. Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses.Academic Press, San Diego, 2011, 203-225 |

Nagai T, Nakamori M. Experimental infection of Ostreid herpesvirus 1(OsHV-1) JPType1, a Japanese variant, in Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas larvae and spats. Fish Pathology, 2018, 53(2): 71-77 DOI:10.3147/jsfp.53.71 |

Norberg P, Kasubi MJ, Haarr L, et al. Divergence and recombination of clinical herpes simplex virus type 2 isolates. Journal of Virology, 2007, 81(23): 13158-13167 DOI:10.1128/JVI.01310-07 |

Oden E, Martenot C, Berthaux M, et al. Quantification of Ostreid herpesvirus 1(OsHV-1) in Crassostrea gigas by real-time PCR:Determination of a viral load threshold to prevent summer mortalities. Aquaculture, 2011, 317(1-4): 27-31 DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2011.04.001 |

Pathirana E, Fuhrmann M, Whittington R, et al. Influence of environment on the pathogenesis of Ostreid herpesvirus-1(OsHV-1) infections in Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas) through differential microbiome responses. Heliyon, 2019, 5(7): e02101 DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02101 |

Paul-Pont I, Dhand NK, Whittington RJ. Influence of husbandry practices on OsHV-1 associated mortality of Pacific oysters Crassostrea gigas. Aquaculture, 2013a, 412-413: 202-214 DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2013.07.038 |

Paul-Pont I, Dhand NK, Whittington RJ. Spatial distribution of mortality in Pacific oysters Crassostrea gigas:Reflection on mechanisms of OsHV-1 transmission. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 2013b, 105(2): 127-138 DOI:10.3354/dao02615 |

Pepin JF, Riou A, Renault T. Rapid and sensitive detection of Ostreid herpesvirus 1 in oyster samples by real-time PCR. Journal of Virological Methods, 2008, 149(2): 269-276 DOI:10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.01.022 |

Pernet F, Barret J, Patrik LG, et al. Mass mortalities of Pacific oysters Crassostrea gigas reflect infectious diseases and vary with farming practices in the Mediterranean Thau lagoon, France. Aquaculture Environment Interactions, 2012, 99(2): 215-237 |

Pernet F, Gachelin S, Stanisiere JY, et al. Farmer monitoring reveals the effect of tidal height on mortality risk of oysters during a herpesvirus outbreak. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 2019a, 76(6): 1816-1824 DOI:10.1093/icesjms/fsz074 |

Pernet F, Tamayo D, Fuhrmann M, et al. Deciphering the effect of food availability, growth and host condition on disease susceptibility in a marine invertebrate.Journal of Experimental Biology, 2019b, 210534

|

Pernet F, Tamayo D, Petton B. Influence of low temperatures on the survival of the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) infected with Ostreid herpes virus type 1. Aquaculture, 2015, 445: 57-62 DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2015.04.010 |

Petton B, Boudry P, Alunno-Bruscia M, et al. Factors influencing disease-induced mortality of Pacific oysters Crassostrea gigas. Aquaculture Environment Interactions, 2015, 6(3): 205-222 DOI:10.3354/aei00125 |

Que HY, Zhang GF. Status and trend of molluscan mariculture techniques in China. Studia Marina Sinica, 2016(51): 69-76 [阙华勇, 张国范. 我国贝类产业技术的现状与发展趋势. 海洋科学集刊, 2016(51): 69-76 DOI:10.12036/hykxjk20160725004] |

Ren WC, Chen HX, Renault T, et al. Complete genome sequence of acute viral necrosis virus associated with massive mortality outbreaks in the Chinese scallop, Chlamys farreri. Virology Journal, 2013, 10: 110 DOI:10.1186/1743-422X-10-110 |

Ren WC, Renault T, Cai YY, et al. Development of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for rapid and sensitive detection of Ostreid herpesvirus 1 DNA. Journal of Virological Methods, 2010, 170(1-2): 30-36 |

Renault T, Arzul I. Herpes-like virus infections in hatchery-reared bivalve larvae in Europe:Specific viral DNA detection by PCR. Journal of Fish Diseases, 2001a, 24(3): 161-167 |

Renault T, Le Deuff RM, Chollet B, et al. Concomitant herpes-like virus infections in hatchery-reared larvae and nursery-cultured spat Crassostrea gigas and Ostrea edulis. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 2000a, 42(3): 173-183 |

Renault T, Le Deuff RM, Lipart C, et al. Development of a PCR procedure for the detection of a herpes-like virus infecting oysters in France. Journal of Virological Methods, 2000b, 88(1): 41-50 |

Renault T, Lipart C, Arzul I. A herpes-like virus infecting Crassostrea gigas and Ruditapes philippinarum larvae in France. Journal of Fish Diseases, 2001b, 24(6): 369-376 |

Renault T, Lipart C, Arzul I. A herpes-like virus infects a non-ostreid bivalve species:Virus replication in Ruditapes philippinarum larvae. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 2001c, 45(1): 1-7 |

Renault T, Moreau P, Faury N, et al. Analysis of clinical Ostreid herpesvirus 1(Malacoherpesviridae) specimens by sequencing amplified fragments from three virus genome areas. Journal of Virology, 2012, 86(10): 5942-5947 |

Roizman B, Pellett PE. The family Herpesviridae:A brief introduction.In:Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, et al.Fields Virology, vol 2. Philadelphia:Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001, 2381-2397 |

Sauvage C, Pépin JF, Lapègue S, et al. Ostreid herpesvirus 1 infection in families of the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas, during a summer mortality outbreak:Differences in viral DNA detection and quantification using real-time PCR. Virus Research, 2009, 142(1-2): 181-187 |

Savin KW, Cocks BG, Wong F, et al. A neurotropic herpesvirus infecting the gastropod, abalone, shares ancestry with oyster herpesvirus and a herpesvirus associated with the amphioxus genome. Virology Journal, 2010, 7: 308 |

Segarra A, Baillon L, Faury N, et al. Detection and distribution of Ostreid herpesvirus 1 in experimentally infected Pacific oyster spat. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2016, 133: 59-65 |

Segarra A, Pepin JF, Arzul I, et al. Detection and description of a particular Ostreid herpesvirus 1 genotype associated with massive mortality outbreaks of Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas, in France in 2008. Virus Research, 2010, 153(1): 92-99 |

Shimahara Y, Kurita J, Kiryu I, et al. Surveillance of type 1 Ostreid herpesvirus(OsHV-1) variants in Japan. Fish Pathology, 2012, 47(4): 129-136 |

Song LS. An early warning system for diseases during mollusc mariculture:Exploration and utilization. Journal of Dalian Ocean University, 2020, 35(1): 1-9 [宋林生. 海水养殖贝类病害预警预报技术及其应用. 大连海洋大学学报, 2020, 35(1): 1-9] |

Song WB, Wang CM, Wang XH, et al. New research progress on massive mortality of cultured scallop Chlamys farreri.. Marine Sciences, 2001, 25(12): 23-26 [宋微波, 王崇明, 王秀华, 等. 栉孔扇贝大规模死亡的病原研究新进展. 海洋科学, 2001, 25(12): 23-26] |

Song ZR, Ji RX, Yan SF, et al. A sphereovirus resulted in mass mortality of Haliotis diversicolor aquatilis. Journal of Fisheries of China, 2000, 24(5): 463-467 [宋振荣, 纪荣兴, 颜素芬, 等. 引起九孔鲍大量死亡的一种球状病毒. 水产学报, 2000, 24(5): 463-467] |

Szpara ML, Tafuri YR, Parsons L, et al. Genome sequence of the anterograde-spread-defective herpes simplex virus 1 strain MacIntyre. Genome Announcements, 2014, 2(6): e01161-14 |

Tang QS, Fang JG, Zhang JH, et al. Impacts of multiple stressors on coastal ocean ecosystems and integrated multi-tropic aquaculture. Progress in Fishery Sciences, 2013, 34(1): 1-11 [唐启升, 方建光, 张继红, 等. 多重压力胁迫下近海生态系统与多营养层次综合养殖. 渔业科学进展, 2013, 34(1): 1-11] |

Tang QS, Han D, Mao YZ, et al. Species composition, non-fed rate and trophic level of Chinese aquaculture. Journal of Fishery Sciences of China, 2016, 23(4): 729-758 [唐启升, 韩冬, 毛玉泽, 等. 中国水产养殖种类组成、不投饵率和营养级. 中国水产科学, 2016, 23(4): 729-758] |

Ugalde SC, Preston J, Ogier E, et al. Analysis of farm management strategies following herpesvirus (OsHV-1) disease outbreaks in Pacific oysters in Tasmania, Australia. Aquaculture, 2018, 495: 179-186 |

Wang CM, Wang XH, Song XL, et al. Purification and ultrastructure of a spherical virus in cultured scallop Chlamys farreri. Journal of Fisheries of China, 2002, 26(2): 180-184 [王崇明, 王秀华, 宋晓玲, 等. 栉孔扇贝一种球形病毒的分离纯化及其超微结构观察. 水产学报, 2002, 26(2): 180-184] |

Wang J, Guo Z, Feng J, et al. Virus infection in cultured abalone, Haliotis diversicolor Reeve in Guangdong Province, China. Journal of Shellfish Research, 2004, 23(4): 1163-1168 |

Wei HY, Huang S, Yao T, et al. Detection of viruses in abalone tissue using metagenomics technology. Aquaculture Research, 2018, 49(8): 2704-2713 |

Wu FC, Zhang GF. Pacific abalone farming in China:Recent innovations and challenges. Journal of Shellfish Research, 2016, 35(3): 703-710 |

Xia JY, Bai CM, Wang CM, et al. Complete genome sequence of Ostreid herpesvirus-1 associated with mortalities of Scapharca broughtonii broodstocks. Virology Journal, 2015, 12: 110 |

Xin L, Li C, Bai C, et al. Ostreid herpesvirus-1 infects specific hemocytes in ark clam, Scapharca broughtonii. Viruses, 2018, 10(10): 529 |

Xin L, Wei Z, Bai C, et al. Influence of temperature on the pathogenicity of Ostreid herpesvirus-1 in ark clam, Scapharca broughtonii. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2020, 169: 107299 |

Zhang FS, Yang HS. Analysis of the causes of mass mortality of farming Chlamys farreri in summer in coastal areas of Shandong, China. Marine Sciences, 1999(1): 44-47 [张福绥, 杨红生. 山东沿岸夏季栉孔扇贝大规模死亡原因分析. 海洋科学, 1999(1): 44-47] |

Zhang QY, Gui JF. Virus genomes and virus-host interactions in aquaculture animals. Science China Life Sciences, 2014, 44(12): 1236-1252 [张奇亚, 桂建芳. 水产动物的病毒基因组及其病毒与宿主的相互作用. 中国科学:生命科学, 2014, 44(12): 1236-1252] |